Passing the Torch to Tomorrow’s Wildland Fire Professionals: Through Mentoring, Training and Pyrotourism

By Steve Miller and Johnny Stowe

When surveying a species you wish to see prosper, it is good to see plenty of mature adults, but just as or more important to see reproduction; without recruitment and also retention, when the older cohorts are gone, a population plummets. And restoring a population is a great deal harder than maintaining one.

In today’s world of increasing socioecological complexity, the need to recruit wildland fire professionals (WFP) for the future is greater than ever. The current demand for WFP far exceeds supply, as is evidenced by regular intercontinental transfer of staff to manage large wildfires. As we venture into what Stephen Pyne has coined the Pyrocene Epoch, the increasing need for qualified, talented and productive professionals will continue.

In “Challenges to Educating the Next Generation of Wildland Fire Professionals in the United States,” Kobziar et al. (2009) propose a career development paradigm. We use Kobziar’s model and others to describe recent and current professional pyropathways, and we propose ways to develop the women and men who are the future of wildland fire.

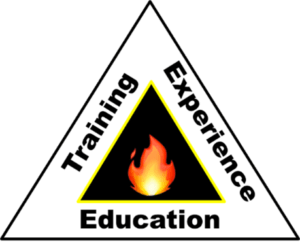

Breaking a concept down into three components as a way to describe physical, and especially social phenomena, is a widespread practice permeating society. Be it in physical or biological sciences or the humanities; advertising and marketing; songs and slogans; or pretty much anywhere you look, you see this tendency. Whether that is simply the way the world often happens to work or because it is a psychologically comfortable and mentally-manageable construct and a useful way of understanding and remembering things, groupings of threes are a valuable mnemonic tool.

Often, we use the figure of a triangle to represent these concepts. We have our basic fire triangle, easily understood by anyone, with the three legs of fuel, heat and oxygen all necessary to have the triangle, and all thus necessary to have any fire, wildland or otherwise. And there are many other triangular concepts within and without the realm of wildland fire.

The Wildland Fire Professional Development Triangle

Kobziar et al. introduced yet another fire triangle: the wildland fire professional development triangle, the three sides of which they define as education, training and experience.

Kobziar et al. 2009

The education leg is typically supported by university and similar programs, while the training leg, as we use the term here, tends to be the more job specific National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) style training provided by agencies in the U.S. Other countries have similar training programs.

The experience leg is doing the work. The challenge for budding WFPs is finding the right balance of the three legs for their particular needs. Job responsibilities vary, and a given job may require much more or much less of one of the legs. But whereas in the fire triangle each leg is vital — and when one is taken away there can be no fire–in our treatment here of the WFP development triangle, in certain jobs, one or more of the legs may be absent and not missed. Generally, though, for young folks preparing for a career in wildland fire, some of each leg is important. Well-rounded preparation provides a wider range of opportunities and advancement.

For countless scores of millenia back into deep-time, and up to the present day, certain people, mostly prescribed burners, have come into wildland fire simply by doing it, by working under the direct tutelage of experienced firelighters who put a torch in their hand and watched over them to keep them safe as they got the job done. Many of the most proficient prescribed burners have little or no education or training, but they safely, reliably and effectively burn woods and grasslands based on deep experience gained through traditional practices and knowledge. When people are indigenous this wisdom tends to be called Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK); for other rural folks who have been living in the same biome, managing the same landscapes, and especially the same ecosystems for many generations, these lifeways have no name of which we are aware. We will propose one. Co-author Stowe began lighting fires over a half-a century ago, burning ancestral lands with his Grandpa, who had learned from his Grandpa in a tradition reaching back through unlettered generations unbroken into the smoky mists of time. Many of his woods-burning ancestors and other elders had no education at all, much less any in wildland fire. It was twenty-five years after he lit his first fires before he found the education leg, learning about the ecology and history of fire in forestry school at the University of Georgia. And only after leaving university did he receive any fire training. His firelighting background might be called Traditional Rural Lifeways (TRL), being based on the lessons passed down by the rural AfroEuropean elders of his homeland.

Co-author Miller was first introduced to wildland fire, both prescribed burning as well as prevention and suppression, in the Texas Forest Service 36 years ago. His 31-year career in Florida included an emphasis on the ecological role of fire and demonstrating to the public the value of controlled burning to reduce destructive wildfires. Over his career, Steve’s on-the-job training and experience led to qualification as Incident Commander. He has worked fire in 18 states and both the northern and southern hemispheres, training many hundred WFPs along the way.

The Times, They Are A-Changing

In contrast to both of us, many of today’s cohort of WFPs are getting education and training before experience. For many agency burns in the U.S. today, increasing levels of training are required. These trends will likely be more pronounced in the future.

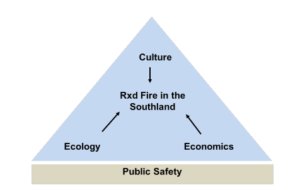

Wildland fire work is a broadly nuanced endeavor, for some people it is their entire job, for others it may be a smaller part of broader responsibilities in professions such as emergency response, wildlife management or forestry. For some it may be about fighting fires–prevention, mitigation and suppression; for others it may be about lighting fires. For many it is about both lighting and fighting fire. And for some it may be a matter of conducting prescribed burns on their own or neighbor’s lands for cultural, economic, ecological or public safety purposes and not a vocation at all. Stowe’s Why We Light Fires Pyramid depicts these goals for prescribed burning.

Catch-22 Conundrums

If someone starts with a fire job early in their career, she may be able to develop very strong experience or training legs but struggle to build a strong education leg. Conversely, those focusing on developing the education leg may have very limited opportunities for gaining experience. Here Catch-22 rears its exasperating head. If someone lacks adequate experience, she may have very limited access to the training leg, because NWCG courses often have task book and experience prerequisites. Sometimes there are significant financial disincentives for WFPs to make mid-career jumps from the experience pathway to the education pathway, and vice versa.

Challenges in finding balance in the three legs of the WFP development triangle are not limited to students and budding professionals. Potential teachers often struggle to provide opportunities for the next generation. And here again, Catch-22 looms large–faculty at universities who wish to offer NWCG training as a part of the curriculum may struggle to gain or maintain credentials necessary to teach the courses. Conversely, WFPs with decades of experience and a great depth of NWCG qualifications may lack the PhD that universities often require.

Progress has been made in the education leg. There are nine universities in the U.S. providing bachelor’s degrees in wildland fire science that are certified by the Association for Fire Ecology (AFE: fireecology.org/afe-certified-academicprograms). Moreover, institutions around the world offer various levels of education and training, and opportunities for gaining experience in wildland fire research, operations, ecology and humanities as part of other programs. Budding firelighters and fighters at the nine institutions above have joined those at 11 other universities to form 20 Student Association for Fire Ecology (SAFE) chapters. https://fireecology.org/safe-chapters.

It is an egregious incongruity, it just ain’t right, that only a single university in Southeastern North America–the birthplace of modern fire science–offers a degree in wildland fire science, although many institutions in the region teach top-notch, wildland fire-related courses and provide wildland fire training and opportunities to gain experience.

John Kush and Kent Hanby taught over a thousand students how to conduct prescribed burns over the last quarter-century in their innovative Auburn University prescribed burning course, the budding burners “settin’ the woods on fire” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F3hzYRVAkUs) on many thousands of acres. Helen Mohr and Wes Bentley of the US Forest Service formed a student wildland fire crew known as the Clemson Fire Tigers to provide training and experience to students while achieving prescribed burning objectives on state and federal lands (https://youtu.be/Wav9ndiZigk). Students from the Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources at the University of Georgia gain valuable controlled burning skills during a spring break field course spent with prescribed firemaster Mark Melvin at the Jones Ecological Research Center, and Martin Cipollini immerses his students at Berry College in controlled burning as well as all other aspects of longleaf pine firelands restoration and management.

The PyroPointers: A Paragon Program and Paradigm for Developing the Triangle and Passing the Torch

Education

The University of Wisconsin at Stevens Point (UWSP) Wildland Fire Science Program is AFE-Certified and connects education to training and experience. We are fortunate to be connected to this paragon program. Students from the Stevens Point campus are called “Pointers.”

Training

UWSP encourages its students to pursue NWCG and other training and certification to make themselves more competitive in the job market. Employers may provide training, but all-else-equal, a well-trained job applicant will have a leg up on her competitors. Students are connected to qualified and experienced fire practitioner-instructors, including co-author Miller.

Experience

The UWSP program recognizes the need to connect education with development of knowledge, skills and abilities, stating “In addition to our integrated curriculum, we strongly encourage and support experiential learning by our students through classroom and field trip experiences, computer simulation models, summer jobs, internships and involvement in student organizations.” (fireecology.org).

The Pointer Fire Crew, which includes students majoring in forestry, wildlife and other disciplines as well as wildland fire science, has established relationships in Florida, Oklahoma and South Carolina to provide students with opportunities for Rxd fire field trips (pyrotourism). Some of these connections have been structured from the top-down by the university, while others have grown through the initiative and energy of students.

Since 2012, teams of students have traveled annually to Florida, volunteering for the Florida Park Service, St Johns River Water Management District and Camp Blanding National Guard Training Base. The students spend a week assisting with prescribed fire unit and equipment preparation, ignition, holding and mop-up. They get experience, work on task books and make valuable contacts.

Since 2013, teams of students have also traveled to Oklahoma over spring break, working on a wide range of tasks on lands owned/managed by the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation and The Nature Conservancy, while interacting with Fire Science Faculty from Oklahoma State University.

The ranching culture of western North America has deep roots in the SE corner of the continent.

Beaches, Burning and Bar-B-Q: How IAWF Yoga led the PyroPointers to the Southland

In 2017, the students added South Carolina to their spring break opportunities, traveling to burn with the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) Heritage Trust Program, setting the woods on fire for both biodiversity and fuel reduction on heritage preserves, and for bobwhite quail management on private lands near the preserves. The fires they light are also part of rekindling a cultural landscape of woods-burning that was first assaulted by the government beginning a century ago and has never fully recovered (Stowe 2017). The SCDNR/UWSP nexus developed through connections made at the 2016 IAWF Conference held concurrently in Melbourne and Portland. Students Paul Priestley, Ethan Robers and Jacob Livingston gave a presentation that we attended in Portland, and then they came to a workshop we hosted, which led to a trip to Powell’s Bookstore. Co-author Miller, a UWSP-trained forester who has maintained close ties to the university, already knew the students, and Stowe connected with them when they attended conference yoga classes he taught at the IAWF’s first wellness program, initiated by the IAWF’s Executive Director Mikel Robinson and her sweet Mom Linda Predmore. Co-author Stowe’s graduate work in environmental philosophy centered on Aldo Leopold’s land ethic, developed when Leopold was professor at the University of Wisconsin, and so when he found the lads were well-versed in Leopoldian reflection, they bonded quickly, becoming fast friends, buddies and colleagues. That led to the students accepting an invitation to come burn with Stowe in South Carolina and the next spring they made the 16-hour drive and arrived “fire-booted and suited” with torches-in-hand, and rearing to go. Their inaugural spring break pyrotourism trip, themed as Beaches, Burning and Bar- B-Q (BB&B), was a huge success and was continued in 2018 and 2019, but C-19 nixed it in 2020. But once things settle down this new tradition will be renewed. We will not let this annual event die!

In South Carolina, students get experiences they are unlikely to get elsewhere. Co-author Stowe has been burning on public and private lands in Lee County for 26 years, and during that time, he has established close relationships with local farmers and landowners, including Jimmy Bland and Whit Player, who manage lands that have been in their families for several generations. The three have formed an informal, local prescribed fire management triangle of sorts themselves, each leg supporting the other, as they help each other with burning and other land management activities. This community connection has been strengthened by a shared love of hunting and local history and the land. Between them, the three partners have over a century and a half of on-the-ground prescribed burning experience, but relatively little training and formal education about wildland fire. Another key partner that the crew has connected with is Gee Atkinson, Editor of the local newspaper, the Lee County Observer

While burning in Lee County, as well as with Jamie Dozier on the SCDNR’s Tom Yawkey Wildlife Center on the Carolina coast (the beach leg of BB&B!), the students learn about participatory land management, experiencing a deeply-rooted, place-based, traditional way of controlled burning that is as much an art as a science, most of it being TRLs not set down in print, and very much different than the rigid, top-down, command-and-control NWCG system. They have invariably adapted quickly–working hard and safely and having fun, learning lots, performing well and getting land burned–while embracing the culture and getting along really well with preserve neighbors and landowners and other local folks. The Harry Hampton Wildlife Fund has provided groceries and Bar-B-Q for the crew, and Jimmy Bland gave the crew a generous donation, while Whit Player lets the crew stay at his family’s cabin. On departing the Southland the crew had the distinction of being christened the PyroPointers and recognized as Honorary Southerners!

Mutualistic Symbiosis and the Cultural Quest for Synergy in Sharing the Flame

Biological symbiosis can be parasitic, commensal or mutual. When managers do nothing to propel the next generation, they play a zero-sum game bordering on parasitism, as if time spent with the next generation somehow takes away from what they perceive as more important work. Mentoring relationships, even relatively effective ones, can also be commensal, with one side benefitting and the other not being impacted significantly either positively or negatively.

Our partnerships with the PyroPointers have been both mutually symbiotic as well as synergistic, with the benefits flowing and growing with each interaction so that the total benefit to each entity adds up to a whole that is a great deal more than the sum of its parts.

In addition to the benefits to the students, we old-timers have gained, among other things: keen, spry, fireline-ready legs to drag a torch, and a rekindling of our fire careers through the crew’s enthusiasm and vigor. We also have the profound joy of helping to shape young minds and lives as we provide them on-the-ground, torch-in-hand experience and training, and of knowing that some of the things we learned from those who passed the torch to us long ago–values and passion and obligation–as well as the things we learned from science and also our mistakes, that some of those things will live on after we are gone. As mentors it’s big-time fulfilling to pass the torch of obligation to the students, instilling in them the responsibility to in their turn Share the Flame with those who are coming along to fill their boots.

The Wildland PyroPathway Ahead

More universities and other educational institutions need to develop wildland fire science programs and student wildland fire crews. We must advocate and promote this growing trend. And as these and similar programs develop, we need to innovate more opportunities for mentoring, field trips and training, and other participatory workways.

Beyond the general need to connect generations of professionals, we need to branch out in other ways. Wildland fire impacts all the world’s diverse cultures to some degree, either directly or indirectly, and as is attested to by the growing interest in and focus on human dimensions research and outreach, wildland fire is no longer largely a matter of suppression strategies, tactics and operations. We must embrace both traditional ecological knowledge as well as traditional rural lifeways; they have much in common that can mesh with modern science to serve our needs. Connecting intergenerationally while reaching across cultures and disciplines is not just a wise, enriching and fulfilling way to move forward, it is an inevitable, emerging, wildland fire lifeway

for our irrupting Pyrocene Epoch.

Share the Flame!

Steve “Torch” Miller retired from the St. Johns Water Management District and now serves as Regional Director of Fire and Aviation Management for the US Forest Service.

Johnny Stowe lights and writes about controlled burning culture and human ecology in Southeastern North America, where he Shares the Flame every chance he gets.

Steve and Johnny serve on the IAWF Board of Directors and are disciples of Aldo Leopold. They met via their mentor, IAWF elder Dale Wade, who connected them in 2005. Mr. Wade continues to inspire, challenge and encourage them as they move closer to the front of the parade. This essay springs from a talk the authors gave at the IAWF/AFE conference in Missoula in 2018.

Resources

Kobziar et al. 2009. Challenges to Educating the Next Generation of Wildland Fire Professionals in the U.S. https://pubag.nal.usda.gov/download/48802/PDF

Miller, S. 2013. Burning in Their Backyards and Having Them Say “Thank You”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0OJcIU2C3FU

Miller, S. 2017. Building a Fire Program that Sustains Ecosystems. AFEx Talk. https://mediasite.video.ufl.edu/Mediasite/Play/1a7c5d1a072844b9bffaf2bab603ee371d

Pyne, S. 2015. The Fire Age. Aeon. https://aeon.co/essays/how-humans-made-fire-andfire-made-us-human

Stowe, J. 2017. Fire-Ties that Bind: The Rekindling of Rxd Fire Culture in North America. AFEx Talk. https://mediasite.video.ufl.edu/Mediasite/

Play/339f90fe77c3494298ad64fdfa10d7ad1d

Stowe. J. 2017. For the Love of Firelighting. Wildfire. IAWF. https://www.iawfonline.org/article/essay-forthe-love-of-firelighting/

Stowe, J. 2020. Fire-ties that Bind: The Natural and Cultural Heritage of Controlled Burning in the Southland and the Rekindling of Global Fire Culture. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HvVcIMFgus&feature=youtu.be

Wade, D., S. Miller, J. Stowe & J. Brenner. 2006. Rx Fire Laws: Tools to Protect Fire: The Ecological Imperative.

https://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/8452

Wade, D. 2011. Your Fire Management Career: Make it Count! Fire Ecology. 7:1. 107-122.

https://fireecology.springeropen.com/track/pdf/10.4996/fireecology.0701107