By Coşkun Okan Güney, Kevin C Ryan, Aylin Güney, and Sharon M. Hood

Millennia of extensive grazing, agriculture, and timber harvesting have altered Turkey’s native vegetation and modified fire regimes. The degree to which this is so is a topic for debate among policy-makers, managers, and scientists – with implications for understanding the potential impacts of land use and climate change on future forest management.

While rapid urbanization, modern agribusiness, intensive forest management, and fire suppression continue to dominate the Turkish landscape, the dynamics of land use and climate change raise questions about the sustainability of future landscapes. How should and how will policy and management evolve to deal with expected increases in wildfires and insect and disease problems? How will these disturbances affect the land’s ability to provide adequate supplies of food, productive soil, clean air, and water as well as increasing demand for outdoor recreation? And what is the role of research and development in informing policy and management changes?

These are the questions – particularly the role of research – that engaged our team’s exchange between scientists from Turkey and the United States, held in Turkey in the fall of 2018. And this is the history and the issues we explored.

The crossroads of nature, culture, and agriculture

Turkey is an ancient crossroads. Surrounded on three sides by water, it forms the bridge between Asia and southern Europe. It is where East meets West and people, their cultures and vegetation merge and mingle. It is a country of great beauty steeped in human history. For a sense of scale, Turkey is nearly the size of California, Oregon and Idaho combined (303,000 square miles vs. 345,000 square miles), with nearly twice the population (80 million vs. 45 million. Located between 36- and 42-degrees north latitude, defined by 4,474 miles (7,200 km) of coastlines, dominated by rugged mountains and the Anatolian Plateau, Turkey has diverse climates and vegetation morphologically quite similar to those found in the three states. Unlike those states, whose mountains tend north and south, Turkey’s mountain ranges tend east and west with increasingly high mountains to the east. It is literally the land bridge formed by tectonic forces. Eighty percent of the land is considered rugged. The average and median elevations are 4,400 feet (1,332 m) and 3700 feet (1,128 m), respectively. In the Asiatic portion flat land is largely limited to the river deltas.

Western Turkey is bordered by the Aegean Sea and the Sea of Marmara. The region has a distinctly Mediterranean climate with mild, wet winters and warm, dry summers. The terrain is generally rolling, a matrix of productive farms and intensively managed forests. The Black Sea region along Turkey’s northern coast is cool and humid throughout most years. The landscape is extensively fragmented by agriculture including orchards and tea plantations. Intensively managed hardwood and conifer forests dominate the higher slopes of the Northern Anatolian Mountains which rise steeply and block moisture from the Black Sea from reaching the interior of the Anatolian Plateau.

On its southern border, the Taurus Mountains also rise steeply from the Mediterranean Sea forming a narrow band of Mediterranean climate.

COASTAL FORESTS. The Taurus Mountains rise abruptly from the Mediterranean Sea. This results in rapid urban-wildland transitions, steep vegetation and fuel type gradients with elevation, and forests dominated by Turkish red pine (Pinus brutia) from 0 to 5,000 ft (0 to1,500 m); European black pine (P. nigra) from 1,300 to 6,900 ft (400 to 2,100 m); and Cedars of Lebanon (Cedrus libani) from 2,600 to 7,500 ft (800-2300 m).

FLAMMABLE SHRUB. The foreground “maquis” shrub vegetation is similar to California chaparral and indicates past fire. The water impoundment is a yangın havuzu (“fire pool”) at 2,382 ft elevation, on the slopes of the 7,762-foot (2 366 m) Mount Tahtali. Such fire pools are strategically placed throughout the Mediterranean region and are a critical resource for initial attack.

Similarly, the Taurus Mountains block moisture from the Sea. As a result, the interior Anatolian Plateau is predominantly a semi-arid shrub-steppe similar to the high deserts of the Great Basin and Columbian Plateau east of the southern Cascade Range of California, Oregon. Summers are hot and dry and winter cold and harsh often with deep snows.

Wheat and barley farming are common on the productive sites while animal husbandry (primarily goats and sheep), alkali flats and terminal (endorheic), saline lakes dominate the less productive sites. And, like the semiarid lands east of the Cascades one might encounter a herd of wild horses (photos below). The Northern Anatolian and Taurus Mountains converge in eastern Turkey with high, inhospitable mountains bosting peaks over 10,000-feet (>3,000m) with Mount Ararat 16,853 feet (5,137m) the highest point in Turkey. These ranges are the headwaters of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers that defined ancient Mesopotamia.

While the similarities of climate, terrain and natural vegetation bear striking resemblance to large areas of the western United States, the scale of intensive farming, forestry and grazing is quite different. As a result of several millennia of intensive land use vs. less than two centuries in the western US, few areas in Turkey could be characterized as “untrammeled by man.”

The rugged topography and history of intensive land use have resulted in a highly fragmented landscape that limits the free spread of fires (photos below), but the land is in transition. Roughly 7 million people live in 22,000 villages located in or near the forests, a drop of 800,000 in the last decade. As is the case in many Mediterranean countries, the decline in traditional land use results in a build-up of fine fuels and an increase in fire potential. Migration of people from rural areas to urban centers stands is in contrast to the influx of urbanites moving into the wildland urban interface of the western US. In recent years, rapidly increasing population and urbanization have increased the pressure on forests for recreational use rather than agrarian subsistence. This is particularly true in the southern and western coastal areas which are preferred by both, domestic and foreign tourists. Around 40 million visitors come to Turkey each year. This change has implications for wildland fuel dynamics and Turkey’s fire prevention program.

Fire management in Turkey today

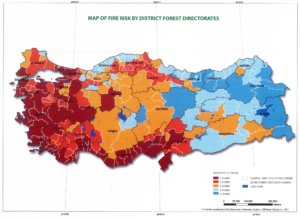

Prevention of forest fires, forest firefighting, and post-fire rehabilitation efforts are managed by the Turkish General Directorate of Forestry (Orman Genel Müdürlüğü, OGM). OGM has gained significant experience in forest fire suppression with relatively successful, trained staff and a management approach that incorporates technology. Approximately 28 percent of Turkey is forested and forest fires are common. In the last eight years, the average number of forest fires has averaged nearly 2,500 fires. These fires burned about 17,000 acres (~7,000 hectares), approximately 7 acres (2.8 hectares) per fire. Eleven percent of fires are caused by lightning. Of the remaining 89% of human-caused fires, the cause for 60% is unknown. In 2018 fire suppression cost $131 million (USD). The greatest risks of fire occur in the Mediterranean climate dominated areas in the south and west (see Risk Map).

FIRE RISK. Fire Risk Map illustrates regional variations in Turkey’s fire environments, ignition risks and the resulting volume of fire business. Risk ranges from “1 Degree” = Highest to “5 Degree” = Lowest. Graphic: OGM.

The average area burned per fire is much less compared to other Mediterranean countries, which reflects quite positively on Turkey’s forest fire-fighting policies and management. The current policy is to initiate an initial attack on forest fires within 15 minutes of detection. The fire detection network, silvicultural practices, extensive road networks and fuel/fire breaks, water impoundments, and air resources render this goal realistic in much of the country. The average time from detection to initial attack has steadily declined from 40 minutes in 2003 to 14 minutes in 2018. Currently, 42 helicopters are available for initial attack.

Turkey’s largest fire occurred in Serik-Taşağıl (Serik-Tasagil, July 31, 2008) burned 38,865 acres (15 795 hectares). This fire lasted for six days and caused heavy damage to many sites, timber loss, and serious erosion. To commemorate large/significant fires and enhance public awareness, roadside museums are often built exhibiting pictures from the fire, from initiation through suppression and post-fire rehabilitation, including primers on fire ecology (photos below).

An International Forestry Training Center, developed and directed by OGM, is located in Antalya (photos below). The Center is a state-of-the-art training facility complete with living quarters where fire managers use computer-based training modules to teach job-based skills for personnel assigned different tasks in forest fire management. Trainees take formal coursework and use realistic fire simulators to develop their operational, tactical, strategic and leadership skills. Over 4,000 Turkish firefighters have trained at the center since it opened in 2013.

The Center provides a forest fire training program not only for Turkish fire management teams but also for participants from other countries. To date, a total of 169 trainees have been trained, representing Bosnia-Herzegovina, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Macedonia, Pakistan, Palestine, Mauritania, Senegal, Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, Niger, Tunisia, and Georgia. OGM also sends teams to help with large forest fires in neighboring countries, for example, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Georgia, Albania, Israel, Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, Libya, Macedonia, Russia, Syria, Greece.

After a fire, the current policy in OGM focuses on intensive efforts to recover timber values and restore burned sites. Burned areas are salvaged and reforested within the first year after a fire. However, concerns about the effects of intensive management on site productivity and future forest development under changing climate and land use are raising questions about the adequacy of current policies to meet the changing needs of the Turkish people.

Given that the need for natural resources is expected to increase in the future, it is increasingly important to know more about the ecological effects of forest fires and to design future management approaches accordingly. Expected climate change, unusual weather events and insect and disease outbreaks might increase the number, size, and severity of forest fires. Therefore, there is a need to understand the fire ecology of Turkey’s ecosystems, both for successful suppression as well as for forest protection and conservation. OGM policy is to use research results to inform management decisions. The Southwest Anatolian Forest Research Institute, which is part of the OGM, has a special emphasis on forest fire research focused on preventing forest fires, reducing fire impacts, and determining the ecological effects of forest fires. Within this context, special attention is paid to the cooperation and science exchange with researchers and institutions that are working in the field of forest fire research from all over the world.

International Collaboration

Within this scope, a forest fire science exchange meeting was held at the Southwest Anatolian Forest Research Institute located in Antalya, Turkey on the Mediterranean coast in October 2018. The meeting was led by Coşkun Okan Güney, forest engineer and forest fire researcher at the Southwest Anatolian Forest Research Institute. Special guests were Dr. Sharon M. Hood from the US Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, and Dr. Kevin C. Ryan, US Forest Service (retired). The exchange was funded by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBİTAK) within the Fellowships for Visiting Scientists and Scientists on Sabbatical Leave Program, with additional support from OGM. The aim of the meeting was to exchange information on fire ecology and forest fire research activities in both countries, to gain knowledge from the American researchers, and to learn their ecological viewpoint which might give direction to future research and collaborations. A variety of researchers from different departments, as well as forest managers and trainers, attended the nine-day meeting.

The meeting started with presentations on the working areas and institutional structures of the US Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station and the Southwest Anatolian Forest Research Institute. Thereafter, presentations followed on fire prevention, fire suppression and post-fire rehabilitation research, development and forest practices in Turkey. The meeting included tours of the fire lab and soils lab at the Southwest Anatolian Forest Research Institute and the fire training simulator at the International Forest Training Center. The meeting continued with mutual presentations, exchange of ideas, and discussions on several topics, including:

- Silvicultural applications for fire management planning, fuel, and ecosystem management

- Determination of fire intensity, fire severity, and fuel consumption

- Post-fire beetle attack and ecological effects

- Prescribed fire, current practices, challenges, and ecological effects

- Post-fire vegetation dynamics and post-fire restoration

- Post-fire tree mortality modeling

In addition to formal presentations, site visits to recently burned areas fostered discussions focused on measuring and monitoring the ecological effects of the fire. Forests reserved for research purposes within the Southwest Anatolian Forest Research Institute were also visited and information was exchanged about current and former studies carried out in these forests. Forest sites included examples of ongoing research on post-fire regeneration and growth and tree mortality for Pinus brutia.

The meeting culminated with discussions of possible cooperation between the US Forest Service and OGM. The aim is to continue communication and establish opportunities for joint collaboration between the two countries. Potential vegetation/fuel and fire ecology research topics within the scope of the Southwest Anatolian Forest Research Institute‘s fire research group were identified:

- Determine the effects of climate change on fire regimes

- Explore the potential use of prescribed fires in fuel management and for fire silviculture

- Model the effects of forest fires using remote sensing techniques

- Map fire risk and determine its relationship with current forest practices

- Monitor and model post-fire vegetation dynamics

- Determine ecophysiological effects of management, climate, and fire on plants

The international exchange provided scientists and managers from Turkey and the United States the opportunity to learn from each other’s experience, identify similarities and differences in approaches to common problems, and develop a bond of friendship.

+ + +

About the Authors

The exchange participants and authors include Coşkun Okan Güney, Southwest Anatolian Forest Research Institute, and Aylin Güney, Department of Biology, Akdeniz University — both from Antalya, Turkey; and Kevin C Ryan, FireTree Wildland Fire Sciences, and Sharon M. Hood, US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station — both from Missoula, Montana, United States.

Photos by the authors unless otherwise noted.