CANADA

THE IMPACT OF FIRE-EXCLUSION LEGISLATION

BY AMY CARDINAL CHRISTIANSON, JANE PARK, ROBERT GRAY, SCOTT MURPHY, KIRA HOFFMAN AND GREGG WALKER

Fire is an important part of many of Canada’s ecosystems. Natural, lightning-caused fires spread regularly across the Canadian landscape. Pre-colonization, Indigenous Peoples applied fire to their territories for a variety of reasons to achieve specific cultural objectives. European settlement of Canada brought a temporary increase in the use of fire for land clearing, settlement, and agriculture, until fire exclusion laws were enacted. Newfoundland was one of the first regions to regulate fire, in 1610; it was declared that no one should set fire to the woods. All provinces and territories eventually legislated fire exclusion, which has resulted in fuel build-up, increased incidence of high-severity fire, increased area burned at high severity, and increased threats to society, the environment, and the economy; this also turned attention, policies, and most of the funding to suppress wildfires.

In the early 1900s, the scientific community began to recognize the need for fire on the landscape and to advocate for the use of prescribed fire. The first use of prescribed fire was for hazard reduction: for example, in British Columbia in the 1910s, prescribed burns were used to remove logging debris, and this activity was institutionalized in 1938 in Section 113A of the provincial Forest Act. In the 1970s, prescribed fire gained more institutional support from fire management agencies, though the scale of actual burning remained relatively small. In a 1992 review of the use of prescribed fire in Canada, M.G. Weber and S.W. Taylor listed six main uses: hazard reduction; silviculture (including site preparation, managing competing vegetation, stand conversion, and site rehabilitation); wildlife habitat enhancement; range burning; insect and disease control; and conservation of ecosystems.

TransCanada highway and was conducted in collaboration with the Town of Banff. Objectives for the burn were wildfire risk reduction for the town,

overwinter habitat for elk and deer, and to stimulate the growth of deciduous trees and valley bottom grasslands. Photo by Jane Park.

Currently, the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre uses the following definitions:

- Prescribed burning – The deliberate, planned, and knowledgeable application of fire by authorized personnel and in accordance with policy and guidelines to a specific land area to accomplish pre-determined forest management or other land use objectives.

- Prescribed fire – Fire deliberately utilized in a predetermined area in accordance with a specified and approved burning prescription to achieve set objectives.

Wildfire management agencies in Canada follow various legislation, acts, and policies regarding the use of prescribed fire, which differs by province and territory. The mandates of wildfire management agencies in Canada often focus on suppression and do not include ecological land management goals. Because of this, agencies with the skills to potentially implement prescribed fire need other government departments and land users to be proponents for prescribed fire. Even so, in large fire years, the lack of resources to conduct the burns and/or attention to high priority wildfires overrides the ability or political will to conduct prescribed fires.

In British Columbia, burn plans are required to be approved by officials as per Section 23 of the Wildfire Act. The preparation and approval of a burn plan can take months to years, depending on the complexity. In Manitoba, most of the burning takes place through the Manitoba Controlled Crop Residue Burning Program on agricultural lands. In Ontario, the Prescribed Burn Policy is governed by several statutes of Ontario and/or policies, including the Forest Fires Prevention Act, the Forest Protection and Prevention Act, the Environmental Assessment Act, the Environmental Bill of Rights, and the Endangered Species Act. Significant changes were made to prescribed fire operations in Ontario after the Esnagami Lake tragedy, during which seven people died as a result of a prescribed fire. The incident and legal proceedings resulted in a long pause to prescribed fire applications. The 53-day inquest into the incident resulted in 36 recommendations outlining how the ministry could improve prescribed fires. Currently, burn application forms must be submitted to the local fire management office, which can take six to nine months to be approved. Once the application is approved, a burn plan needs to be submitted at least 60 days in advance for low-complexity burns and 75 days in advance for high-complexity prescribed burns before the intended ignition date. The plans must be fully approved 30 days before an ignition, and no major changes can be made within 14 days of the burn.

According to Kira Hoffman and colleagues in a 2022 paper “Western Canada’s new wildfire reality needs a new approach to fire management,” the use of prescribed fire has decreased over the 25 years in British Columbia due to increased regulation (including problems with agency approval processes and timelines), smoke concerns, fear of escapes, and a lack of qualified and experienced practitioners. There is no prescribed fire certification framework in Canada: The Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre does not have any prescribed-fire related certification, so people lean on U.S.-based certifications that do not apply. The only prescribed fire planning course is offered by Parks Canada and Alberta, but limits enrollment numbers. Because there is prescribed fire training/certification, people who largely conduct ignition for wildfires (during increasingly extreme burning conditions) are seen to have expertise to put prescribed fire on the landscape. However, those skills don’t translate to the art/science of burning in less volatile conditions, and those who are certified may lack the intimate knowledge of ecological fire effects and habitat needs for various organisms/ecosystems.

have included creating grizzly bear habitat, increasing ungulate habitat, promoting five-needle pine, reducing mountain pine beetle impacts,

and wildfire risk reduction.. Photo by Jane Park.

Hoffman and colleagues point out there has been an increased interest among wildfire management agencies and the public in cultural burning conducted by Indigenous Peoples. However, a 2022 paper by Hoffman and other colleagues “The right to burn: barriers and opportunities for Indigenous-led fire stewardship in Canada,” shows many barriers exist to prescribed fire and cultural burning including a lack of understanding, governance, regulations, accreditation, training, liability, insurance, capacity, and resources.

PARKS CANADA

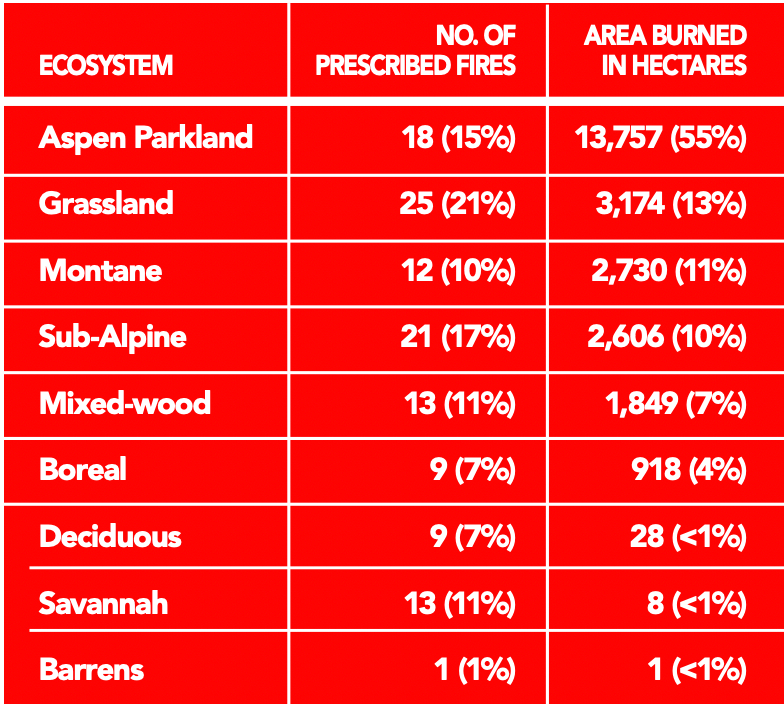

Parks Canada is an outlier in terms of use of prescribed fire by wildfire management agencies in Canada. Parks Canada has used prescribed fire since the 1970s in national parks and at historic sites to reduce wildfire risk, promote more resilient landscapes, and restore and maintain ecological integrity and cultural landscapes. Parks Canada conducts prescribed fires in all ecosystem types (Figure 1). Some specific burn objectives have included creating grizzly bear habitat, increasing ungulate habitat, promoting five-needle pine, reducing mountain pine beetle impacts, and wildfire risk reduction. In recent years, Indigenous knowledge of fire has become more widely recognized and cultural burning practices are being supported in certain parks, including the Gulf Islands National Park Reserve where Indigenous partners and the park are revitalizing cultural burning practices for Garry oak ecosystems.

Despite actively using and supporting prescribed fire, there are still relatively small numbers of prescribed fires and area burned per year compared to wildfires. Parks Canada statistics on prescribed fire and wildfires show that since 1981, the annual number of prescribed fires has been highly outpaced by wildfires. For example, the largest number of prescribed fires Parks Canada has conducted in one year was in 2015, when there were 28 prescribed fires but 122 wildfires. The amount of area burned annually by prescribed fires since 1981 varies from 100 hectares to 11,000 hectares and is highly dependent on weather conditions. It is important to note that Parks Canada has conducted prescribed fires consistently since the late 1990s, unlike other agencies, which have reduced the numbers of prescribed burns.

burned across all sites, 2009-2018.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Amy Cardinal Christianson is an Indigenous fire specialist with the National Fire Management Division, Parks Canada.

Jane Park is a fire and vegetation management specialist for the Banff Field Unit, Parks Canada.

Robert Gray is an AFE certified wildland fire ecologist and the president of R.W. Gray Consulting Ltd. Scott Murphy is a national fire management officer with the National Fire Management Division, Parks Canada.

Kira Hoffman is a fire ecologist who is a jointly appointed postdoctoral fellow at the University of British Columbia and The Bulkley Valley Research Centre.

Gregg Walker is a fire scientist with the National Fire Management Division, Parks Canada.