After Action: an occasional column by fire practitioners and scientists who offer observations and reflections from the field.

By Johnny Stowe

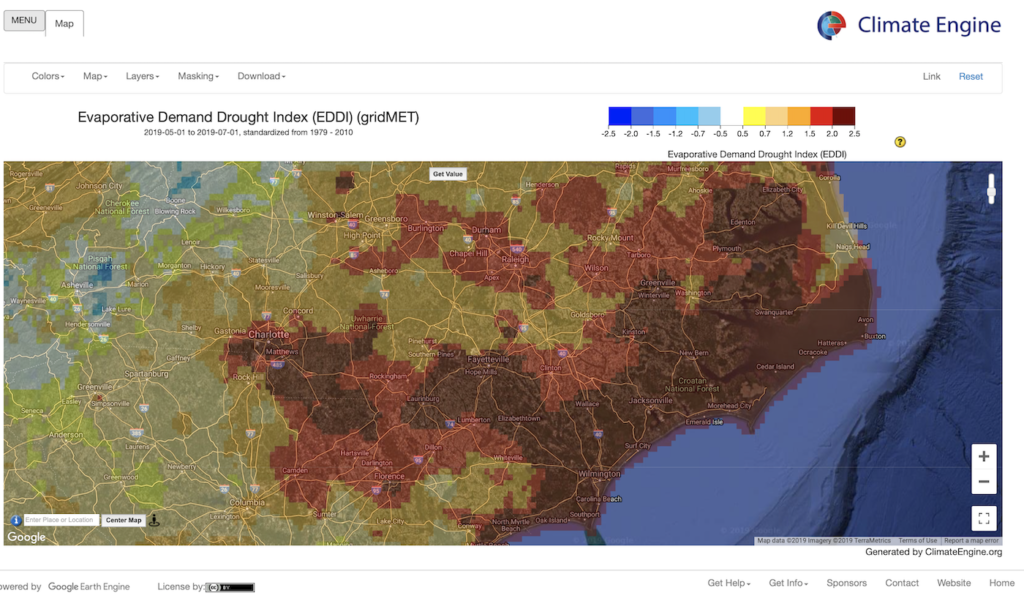

Some longleaf pine trees are again shedding their needles early across the Carolinas and Georgia this year. Needle cast is an annual, natural occurrence usually taking place in autumn, but sudden, extreme drought has combined with high temperatures to cause this to take place early in certain areas.

Many folks become alarmed when they see brown needles on longleaf pines, since the trees are, after all, classified as evergreen. But the term evergreen can be misleading.

Although longleaf pines do retain some needles year-round, in years with normal rainfall individual bundles of needles generally remain on the tree for two growing seasons and are shed in the fall.

In several years with low rainfall over the last decade many longleaf pines dropped their needles in late July. But I have never seen healthy longleaf pines drop needles before the June solstice. This year I noticed needles on scattered trees in the Carolina and Georgia Sandhills browning up the last week in May.

Severe stress like this may cause some trees to die if other stress factors are in place or come along before the trees can recover from this episodic drought stress.

The two-year-old needles on longleaf pines are closer to the base of the branches than the younger needles, and so one easy way to tell if browning needles are a cause for concern or not is to note where they are found on the branch. If needles are browning at the base of branches but the needles toward the end of the branches are green, then the “brown-up” is either a result of annual fall shedding, or if it happens before fall, it is likely a natural response to drought. If the needles are browning at the extreme ends of numerous branches, especially if they are toward the top of the tree, then the problem might be something other than drought stress.

By dropping needles early, the tree reduces its need for water. Wilting of leaves in many other plants is a similar response to drought but differs in that the wilted leaves usually remain on the plant.

By wilting, leaves expose less surface to the sun and wind and so the plant requires less water. If the stress is not too severe or of not too long a duration, wilted leaves can recover when the plant receives additional water. Corn, which is a member of the grass family, curls its blades (leaves) to reduce water loss. This is often called “twisting,” and is easy to see. The blades of native warm season bunchgrasses, including Eastern gammagrass, also twist to reduce water loss, but they are much more resilient to drought stress because they have extensive root systems. If rainfall comes in time, grass blades will unfurl, otherwise they will die.

But browned needles are dead and do not reverse to green. The browned needles will adhere to the branches at first but eventually fall from the tree, usually dropping during high winds.

Trees are efficient at taking up, conserving and recycling nutrients. Before pine needles are shed in the fall, a high percentage of the nitrogen and phosphorus in the needles moves back into the tree before the needles turn brown and fall off. Nutrients such as calcium and magnesium do not translocate when needles shed. So these nutrients may be lost from the site in substantial quantities when straw is commercially raked on a regular basis. In those situations, it may be beneficial to fertilize occasionally to offset the loss of nutrients, especially on poor land where longleaf pine often grows. Soil tests or foliar analysis can reveal any nutrient loss.

Trees responding to unseasonal drought stress may not have time to extract nutrients before the needles brown up.

Individual trees may drop needles a few weeks apart. Trees on dry sites tend to drop needles earlier than trees on wetter sites. Sometimes, trees growing on the same site next to each other drop needles at different times. Other species of pines, such as ponderosa pine, tend to react similarly to drought. Timing and degree of needle cast can impact fire behavior in nuanced ways that are dependent on age of trees, stand density, fire history and other site characteristics.

Longleaf pine ecosystems are fire-dependent forests, woodlands and savannas that once covered 25-35 million hectares from Virginia to Texas and down into Florida. The ecological integrity of these ecosystems, including high levels of biodiversity, is dependent on fire every one to five years. As it becomes increasingly impractical to allow lightning-ignited fires to burn, prescribed fire is serving a larger role. Prescribed fire lighters ignite about 500,000 acres per year in South Carolina, but more land needs to be burned in the state to enhance and sustain public safety, and for economic, ecological and cultural benefits.

Besides being more drought-resistant as compared to other Southern pines, longleaf is also less susceptible to damage from wind, fire, insects and diseases.

Repeated and relatively-sudden changes in established seasonal or annual phenomena such as needle cast may be a harbinger of long-term weather patterns, and have implications for climate change. Other phenological phenomena include time of first and last frost, snowfall, rainy and dry seasons, and spring “green-up” when leaves begin to grow. Timing of animal migrations and breeding, insect life stages, and the shedding of velvet and antler cast in deer are easy-to-observe phenological occurrences.

This is the news from our changing climate, circa 2019, from the land of the longleaf pine.

+

Resources

Evaporative Demand Drought Index, May 1 to July 1, 2019, focused on Longleaf Pine habitat. https://climengine.page.link/3N7d.

“Estimating canopy fuel characteristics for predicting crown fire potential in common forest types of the Atlantic Coastal Plain, USA.” Anne G. Andreu, John I. Blake and Stanley J. Zarnoch. International Journal of Wildland Fire 27(11) 742-755 https://doi.org/10.1071/WF18025.

“Modeling climate change, urbanization, and fire effects on Pinus palustris ecosystems of the southeastern U.S.” Jennifer K. Costanza, Adam J. Terando, Alexa J. McKerrow, Jaime A. Collazo. Journal of Environmental Management. Volume 151, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.12.032

+

About the Author

Johnny Stowe is a Heritage Preserve Manager in the Catawba district, South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, and a board member of the International Association of Wildland Fire. He joins Wildfire as a contributing editor.