It’s just past mid-fire-season in parts of Australia and this fire continent has already burned beyond what’s been experienced in our lifetimes.

Our coverage will continue in future issues of Wildfire. For now, we share these updates — as told in a gallery of images, commentary by Richard Thornton, a memorial for fallen firefighters, and links to hazard outlooks, fire and weather monitoring, and background science (below).

+

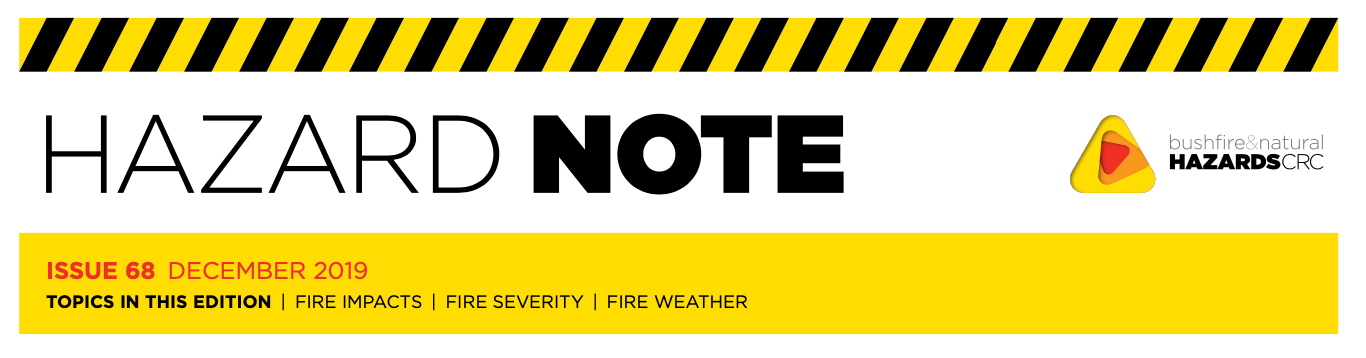

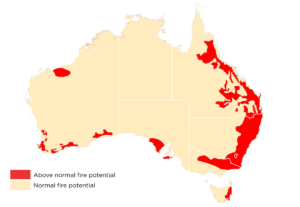

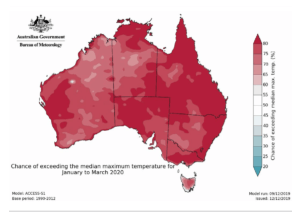

As the mid-December “Hazard Note” predicted for Australia, drought and heat waves are extensive, record-setting, and likely to continue into March. With 2019 the hottest and driest on record for Australia, what began as a challenging fire season has burnt 10.7 million hectares (26 million acres) as of January 8, 2020, with 29 fatalities reported and an estimated 2200+ structures burnt. And this long season is likely to burn longer than normal.

From Hazard Note 68…

With the combined hot and dry conditions in place it is not surprising that the southern fire season started early and has been severe to date. Large areas have seen record fire danger overall, as well as a very early start to the high fire danger period. In area average terms, the fire weather as measured by the Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI) for spring was record high for Australia, as well as all states and territories apart from South Australia (second) and Victoria.

The tendency for fire seasons to become more intense and fire danger to occur earlier in the season is a clear trend in Australia’s climate, reflecting reduced and/or less reliable cool season rainfall and rising temperatures (see State of the Climate 2018). Fire season severity is increasing across much of Australia as measured by annual (July to June) indices of the FFDI, with the increases tending to be greatest in inland eastern Australia and coastal Western Australia.

While both climate drivers [the positive Indian Ocean Dipole pattern and negative Southern Annular Mode] are likely to decay by mid-summer, their legacy will take some time to fade. The positive Indian Ocean Dipole and the dry conditions experienced in winter and spring are known to be associated with a more severe fire season for south east Australia in the subsequent summer.

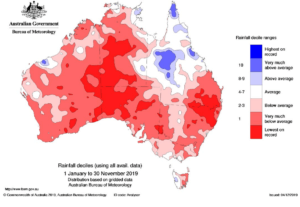

The rainfall outlook for January to March (Figure 4) suggests that rainfall is likely to be above average in western areas, while eastern Australia generally sees odds which are close to 50:50. The decay of the Indian Ocean Dipole means that probability swings are less strong than earlier in the season for eastern areas, suggesting that some relief in dry conditions is possible in the coming months.

Tracking fire & weather (selected links)

FIRE ACTIVITY & RISK

Digital Earth Australia Hotspots: https://hotspots.dea.ga.gov.au.

MyFireWatch (satellite mapping): https://myfirewatch.landgate.wa.gov.au/map.html.

New South Wales (NSW) Rural Fire Service, Fire Information: http://www.rfs.nsw.gov.au/fire-information and https://www.rfs.nsw.gov.au/fire-information/fires-near-me.

Victoria Country Fire Authority: https://www.cfa.vic.gov.au/warnings-restrictions/total-fire-bans-and-ratings.

WEATHER

Australia Government. Bureau of Meteorology. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/outlooks/#/overview/summary.

SPEI Global Drough Monitor. https://spei.csic.es/map/maps.html#months=1#month=11#year=2019.

+ + +

Exploring the Science

How can fire science help us understand a record fire season? A search of “Australia” in the International Journal of Wildland Fire (https://www.publish.csiro.au/WF/search?q=australia&sjournal=on) pulls up 209 articles that help connect the science with the fires. A sampling of topics (by no mean complete) explores questions about this fire season and may help prepare for future seasons.

For instance, we can ask what combinition of extreme fire and weather may lead to a fire season this intense, and find that Harris et al discovered that “Most of the life and property losses due to bushfires in south-eastern Australia occur under extreme fire weather conditions – strong winds, high temperatures, low relative humidity (RH) and extended drought.” They observe that “what constitutes extreme, and the values of the weather ingredients and their variability, differs regionally.”

“Variability and drivers of extreme fire weather in fire-prone areas of south-eastern Australia.” Sarah Harris, Graham Mills and Timothy Brown. 13 February 2017. 26(3) 177-190. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF16118.

There are a range of aritcles on fire and climate, and Clarke et al concluded that by 2100, “Based on these changes in fire weather, the fire season is projected to start earlier in the uniform and winter rainfall regions, potentially leading to a longer overall fire season.” Their research explores the models and why more intense fire seasons may become a more common pattern.

“Regional signatures of future fire weather over eastern Australia from global climate models.” Hamish G. Clarke, Peter L. Smith and Andrew J. Pitman. 20(4) 550-562. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF10070.

And with houses lost (and many more saved), research into what conditions are more likely to lead to house loss is key. Blanchi et al analyzed 54 bushfires between 1957-2009 that resulted in nearly 8300 houses burned. The key observation: losses occur when the McArthur Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI) is over 100. Observe that “Virtually all of the house loss has occurred above the 99.5th percentile level in the distribution of daily FFDI for each of the regions considered.”

“Meteorological conditions and wildfire-related house loss in Australia.”Raphaele Blanchi et al. 05/11/2010. 19 (7). https://doi.org/10.1071/WF08175.

To explore and understand the “why” of extreme fire behavior in Australia, this BNHCRC Core Project page for “Threshold conditions for extreme fire behaviour,” which features a research team, including fire-manager end-users … that is “investigating the conditions and processes uwnder which bushfire behaviour undergoes major transitions, including fire convection and plume dynamics, evaluating the consequences of eruptive fire behaviour (spotting, convection driven wind damage, rapid fire spread) and determining the combination of conditions for such behaviours to occur (unstable atmosphere, fuel properties and weather conditions).” Read more at https://www.bnhcrc.com.au/research/understanding-mitigating-hazards/1300.