Crafting a fire system for the future

A perspective on matching modernization with changing complexity in our Wildland Fire Management System

By Tom Zimmerman and Joe Stutler

-

Today’s situation, tomorrow’s destination – a more challenging complexity

Today’s society exists in a continuum of weather, climate, vegetation, social and economic values, and political concerns that places enormous influences on wildland fire. Understanding the interrelationships involved in this is a critical step in comprehending the complexity surrounding wildland fire management.

Significant changes are taking place today, most of which are dramatic and rapid. Modified wildland fuel complexes, expanded wildland-urban interface (WUI) areas, increased human-caused fire numbers, changing climatic conditions, altered fire regimes, and shifting social/cultural perspectives provide little doubt that we are in a period of worsening complexity. These changes are triggering extensive and uncompromising, shifts in the behavior, extent, and effects of wildland fires and it can be easily seen that the degree of difficulty in accomplishing wildland fire management objectives is becoming immeasurably more complicated.

The subsequent wildland fire impacts to social, management, economic, and political values present far-reaching management challenges. Demands on and expectations of decision-makers and responders are rapidly mounting and firefighter risks and suppression costs are reaching unprecedented levels. These trends are not necessarily new, but the erratic nature and speed of change now taking place are becoming increasingly alarming.

To more effectively respond to complexity, the wildland fire management program must be viewed as a wildland fire management system and evaluated in terms of how well it can meet future challenges. The state of the program may be considered well positioned to move into the future as fire knowledge; science, technology, and operational capability; policy maturation level; and the understanding of management strategies and tactics have never been more complete. But, while many actions have been planned and implemented with countless successes realized, the future is necessitating intensified and diversified actions to keep pace with changing conditions and shifting complexity. The wildland fire management system must be modernized at a rate greater than that of increasing complexity. Decisions and actions must be adapted, the body of knowledge must be enlarged, experience must be expanded, and capabilities boosted. There is much that can and should be done to ensure sustained stability and success in the wildland fire program.

What the future challenges will be and how they will be responded to are powerful and thought-provoking unknowns. While the answers are uncertain at this time, this paper offers questions about capability, discusses wildland fire management as a fire management system, and provides thoughts on opportunities for advancing the wildland fire management system to keep pace with changing complexity and better meet future challenges.

2. A Wildland Fire Management System – anchored in Cohesive Strategy

A number of elements influence wildland fire management. Those that shape program direction, program structure and function, and planning and implementation are most influential. These include the framework of policies, strategic plans, land and resource management plans, and other guiding documents. They provide program guidance, expanded flexibility, and the structure to keep pace with a dynamic situation, while embodying the state of the knowledge, the state of the art, and the latest science and technology.

Flexibility in program direction is extremely important since a viable one-size-fits-all management option does not exist and even if it did, is not desirable.

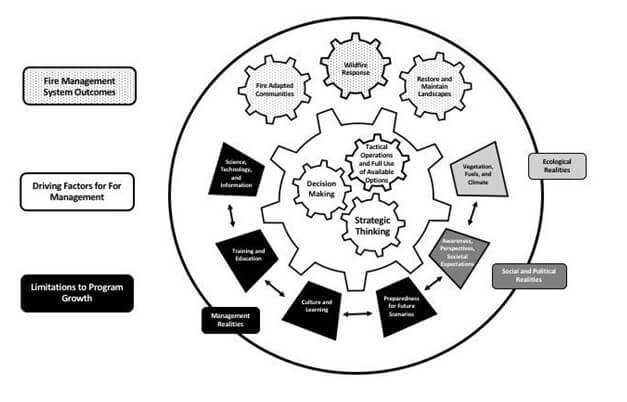

Each year, escalating complexity and experience bring “new firsts” that increase appreciation of change and awareness that wildland fire management must be viewed as a complex system. While other articles discuss this approach, (Thompson et.al. 2018: Christiansen 2019), we frame our discussion of this system in terms of three principal components: strategic goals as system outcomes; functional drivers of the system; and factors limiting the system (Figure 1).

The strategic goals from the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy (USDI-USDA 2014) can be viewed as outcomes from the wildland fire management system and comprise the top portion of Figure 1, shown in a patterned fill. These goals provide a full range of flexible outcomes, set the stage for a wide range of actions, promote multi-focus thinking, and provide for a range of comprehensive objectives.

We identify three functional elements as primary driving factors of the system (Figure 1). They consist of strategic thinking; decision-making; and tactical actions and full use of available options, which are shown in the center of the figure in white. It has been stated that outcomes of the fire management system are driven by a suite of environmental, social, political, financial, and cultural factors (Christiansen 2019). But, we view these in terms of realities that are highly important due to their influence in restricting program development and advancement. These consist of management realities, social realities, and ecological realities, shown in the lower portion of Figure 1 in solid colors.

From this view of the fire management system, it is clear that the desired range of outcomes is dependent on the three primary driving factors. These driving factors are highly intertwined and must function in coordination with each other to make the system work efficiently. But they can be limited by many aspects of management, social and political, and ecological realities. These realities, individually or in concert, can very quickly become barriers to program function by limiting any of the three driving factors (Figure 1).

3. Is modernization needed to meet challenges and match complexity?

A solid framework and the right tools and processes currently exist, but continued forward movement must build on emerging tools and processes to modernize capabilities. Progress must be monitored and assessed to ensure focus is not lost and energy is not wasted. Every opportunity must be evaluated and acted on. Failing this, the program will lapse into passive management fueled by a flawed thought process. This faulty approach will not succeed in the future; it will allow challenges to overwhelm managers and force reactionary decisions and responses without sufficient forward-thinking.

Awareness of this situation is increasing. Christiansen (2019) highlights opportunities to improve the wildland fire management system, states that a new approach is needed and reinforces how the Cohesive Strategy is providing more opportunities for improvement. Bosworth and Williams (2018) advocate for a more imaginative approach to wildland fire management and Thompson et al. (2018) support reevaluation of the fire management system.

To be progressive in management and implementation, there are some certainties that cannot be ignored if specific answers about future direction are to be found. Table 1 provides a list of these certainties associated with wildland fire management today and pertinent questions for the future.

Table 1. Uncommon certainties of today and questions surrounding tomorrow’s wildland fire management.

| Certainty | Questions for the Future |

|---|---|

| Over-indoctrination with unwise information places excessive pressure to see truth. | -Is the changing complexity of wildland fire management fully understood? -Is changing complexity being ignored due to historic fire management culture? |

| Change is hard and pervaded by reluctance to accept, and put into practice. Repeated practices do not cease to be ill-advised simply because they have long been accepted as the norm. | -Does the capability, and will, for developing and implementing the necessary operational change exist? -Is a passive management stance letting changing conditions drive decisions and actions or is active decision-making being used to influence change and help field better responses? -Are new perspectives being heard and recognized? |

| Investing in the future is not foolish but is perhaps the most valuable contribution. | -Are employee skills and agency capabilities being advanced? -Are future skill, education, and training needs being anticipated and prepared for? |

| Great leadership does not mean ignoring reality.. | Is the wildland fire management system being modernized at a rate commensurate with increasing complexity? -Are strategic thinking, precise tactical actions using all available options, optimal use of prescribed fire and fuel treatments, science and technology, up-to-date and imaginative training, and upgraded processes to improve decision-making and implementation being incorporated into management at the proper rate? -Are new capabilities, knowledge, and opportunities being endorsed? -Are decisions reflecting commitment to safety by actively incorporating risk management? -Is active learning occurring and based on the best information? |

To answer these questions, attention must be given to the three driving elements of the wildland fire management system to provide clarification that modernization must be reflected in these areas and priorities must be identified.

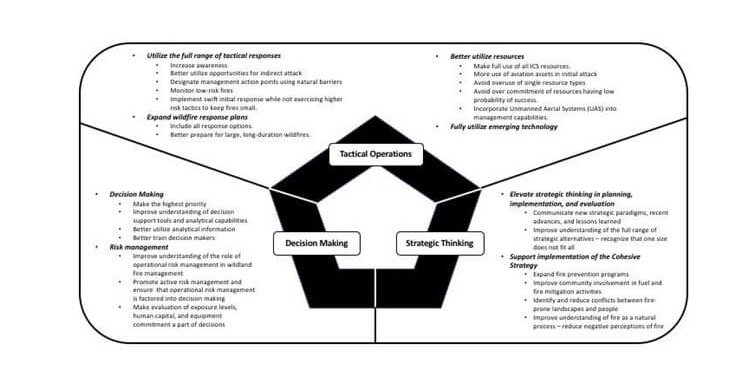

Strategic Thinking: Strategic thinking enables focus and drives active, progressive, and long-term assessment and action. It powers both decision-making and implementation of tactical actions. Without strategic thinking, decision traps such as over-reliance on past experience, over-emphasis on a specific tool or process, seeking a single and simple answer or a “one size fits all” management action, or lapsing into single-focus thinking and action will result.

Decision Making: Decision making directly influences tactical actions and provides feedback to strategic thinking. Completing the most thorough review of a situation, developing a set of potential actions, and making risk-informed decisions are dependent on the collection and analysis of information. New strategic and tactical paradigms, recent advances, and lessons learned must be valued, comm

unicated, and understood by decision-makers, their organizations, and the public.

A principal limitation of decision-making support is not the direct weakness of information but comes from the emphasis placed on it and its degree of use. It is far too easy to overlook, misunderstand, or resist applying the best available information. Time constraints can negatively affect decision creativity, foresight, and quality. It has not been uncommon for decision-makers to review and superficially embrace decision support information, which might be unmistakably relevant, then fail to incorporate or utilize it in the decision process simply because it is new, outside an experience zone, or spontaneously considered too hard to understand. Also, while a review of historic activity can also be extremely important, many decision-makers do not have the luxury of personal knowledge of past events in a particular area. Consequently, they may get caught up in a contemporary bias that places too much emphasis on the most recent or immediate information and fails to recognize potential precedent-setting earlier events, a temporal tradeoff where sufficient actions are not done quickly enough, or a decision transfer where belief in alternative action sets is given too much weight, regardless of available information.

But, there is also a downside that must be considered. Information availability must be balanced so that information overload or overemphasis can be avoided. Decision making must not become a burden on managers. It should not be pervaded with inflow of so much information that it becomes a question of “what do I have to know?” It should be about acquiring information to answer the question of “what can I use to advance my awareness, understanding, and make better decisions?”

Tactical Actions and Full Use of Available Options: Wildland fire response capability has grown to become very sophisticated and efficient and accomplishes early control of most unwanted wildfires. Despite strong capability and efficient operation, a small percentage of fires escape initial response and become large and often, long-duration fires. This proportionately small number of fires are responsible for a disproportionate amount of area burned, damage to homes and infrastructure, personal injuries and loss of life, and incur the bulk of annual suppression costs.

Tactical responses to wildland fires must be coordinated, well thought out, and efficiently directed to safely accomplish desired objectives. Initial responses can be successful within their designed capabilities, but for those fires that escape initial actions, specific situational analysis and use of the full range of options must be considered and applied. Continuing to apply failed tactics or over-utilizing a particular tactic or type of firefighting resource, regardless of the specific situation, does not further protection objectives, but increases costs and exposes firefighters and equipment to increased risk and exposure. Employing costly tactics repeatedly and increasing expenditures have not been shown to increase suppression effectiveness (Calkin et al., 2014).

Changing conditions do not alter the direction for safely and effectively extinguishing fire when needed; using fires where allowable; and managing our natural resources by making use of all available options.

It is clear that within these three driving factors, there are a number of opportunities for modernization efforts. Many, but likely not all, are shown in Figure 2.

4. Today’s realities, tomorrow’s impacts lead toward modernizing the Wildland Fire Management System

Changing conditions and emerging situations are challenging conventional thinking and standard practices. This is not unique to the United States, but one that is pervasive to all fire organizations around the world. The magnitude of change that is taking place has brought us to a point in time warranting a hard and in-depth look at whether forward program movement is commensurate with changing complexity or if operation under an old model continues. There are a number of reports that contend that changes are not being responded to purposefully and quickly enough (Thornton 2020; Kolden 2019; Raines and Harbour 2018; Thompson et al., 2018; Calkin et al., 2015).

The most recent fire season in Australia in 2019-2020, one that exceeded all others, has already and continues to generate considerable introspective analysis of the overall fire situation and response capability. Thornton (2020) offers a commentary on this fire season and believes that what is needed is a quantum shift in thinking. He emphatically submits that to pursue the same path under the current system is merely a simple solution to a complex problem, and wrong!

Raines and Harbour (2018) state that current and past practices in wildland fire have contributed to an untenable and unstable situation that without important changes will not remain static but will worsen. They submit that change is coming, either through natural on-the-ground events or through organization shifts; the status quo will not continue.

Other authors have stated that without significant social and managerial changes, the future of wildland fire management in the western United States will perpetuate “business as usual” (Calkin et al. 2015; Ingalsbee 2017), and likely result in continued increases in costs, damages, and serious injuries (Thompson et al. 2016). Such outcomes only stifle opportunities for meaningful change and represent the rationale for rethinking the wildland fire management system (Thompson et al. 2018). In addition, continuing with the current system as is will not support heightened integration of risk assessment and management but lead to prioritization of management for short-term risks during wildland fire events (Schultz et al., 2019).

To most efficiently bolster the wildland fire management system, attention must be focused on those areas having the strongest influences on the system. Looking at factors that limit the ability of strategic thinking, decision making, and tactical operations to function at high levels, it is readily apparent that management realities, social and political realities, and ecological realities surface as the prime foci that can quickly limit or block efficient operations.

Management Realities. Management realities consist of factors having strong influence on management activities and arise from management structure and function. There are four main areas of management realities that we would like to touch on which include: research, science, technology, and information systems; training and education; culture and learning, and preparedness for future scenarios.

Research, science, and technology, and information systems: Throughout the history of fire management, research, through systematic investigation, information collection, and analysis, has communicated enormous quantities of new science and technology, positively informed action, validated policy development, supported management programs, and shaped the understanding of wildland fire. Notwithstanding these gains, current and future challenges dictate that knowledge of wildland fire and its interrelationships with the environment and society; its foundational inclusion of risk management, its support to strategic direction, and its influence on overall management capability must be increased (Hall et al., 2018).

This is a time where decreased attention and commitment to research is untenable. Making science, technology, and information management significant leverage points in support of program implementation must be a priority goal (Thornton 2020; Cissel and Zimmerman 2018). Accelerated and well-conducted research programs are more vital to the success of wildland fire management endeavors than ever before. Science, especially research conducted in a cooperative manner, will assist in strengthening fire and land management (Hall et al., 2018).

What can be done?

- Present a strong and definitive leaders’ intent to make continuing and accelerating research a greater priority so wildland fire science can move forward as an organized body of knowledge and improve the application of science information for practical purposes.

- Increase research program budgets to support continued and accelerated work.

- Increase science delivery and translation across agency programs and make outcomes more accessible, useful, and actionable.

- Update data sets, advance technology, and expand audiences so that wildland fire science can more readily support and improve planning, implementation, and decision-making processes.

- Continue research to identify ways to contain/manage large wildfires more efficiently and identify where large, long-duration wildfires are likely to occur.

Training and Education – Advancing Knowledge: Better preparation of personnel to meet emerging challenges must involve greater diversity in training delivery methods as well as on-the-job training and education based on the most current and relevant information. Decision makers and planners must be prepared to manage the complex risk management and strategic planning tasks associated with response to wildland fires. Serious questions exist whether this is occurring through appropriate training and experience (Schultz et al., 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic and its ramifications to moderate to large group gatherings renders the traditional training model where trainees gather at a single location for in-classroom training mostly unusable. Greater use of virtual training delivery and off-site education will have to be pursued if training and certification standards are to be met.

What can be done?

- Ensure that training and education courses provide current information; relate to current situations; match knowledge, technology, and practices with fire complexity; and that coursework is developed/revised as situations warrant in a timely and proactive manner.

- Update training courses on a more frequent schedule to be more inclusive of changing situations and emerging information.

- Rapidly identify new or additional skills needed.

- Prepare tailored learning to fill skill gaps.

- Make full use of all available training delivery methods – give equal or greater emphasis to virtual training and remote self-study.

- Adopt fully digital approaches to re-create the best in-person learning through live video and social sharing (Agrawai et al. 2020).

- Reskill workforces to better prepare to live in a new working environment – train for work in a digital and remote environment.

- Expand the ability to operate in a fully digital environment – “stay ahead of the curve.”

- Strengthen awareness of digital collaboration.

Culture and Learning: To better respond to a changing and challenging paradigm, it is important to advance knowledge levels, facilitate and take advantage of learning opportunities, and heighten all management capabilities. Wildland fire management must be a true knowledge and learning program where constant attention is given to emerging information, new knowledge, past experiences, historical documentation, and lessons learned.

Over-reliance on passive management, characterized by over-dependence on historical experiences and hindsight bias; failure to accept new processes; continued use of failed strategies and tactics; dated training and education; and slow learning or total disregard for lessons learned must be avoided. Knowledge, training, and education must reflect the state of knowledge and experience and information must be accessible and communicated to the greatest extent possible.

Organizational culture is the collection of assumptions, values, beliefs, and principles which gives a clear picture and motivation to people as how they and the organization behave. It includes an organization’s vision, mission, guiding documents, stories, values, beliefs, policies, and habits. It affects the total motivation of people. Wildland fire management culture arose from early beliefs that all wildland fires were detrimental to natural resources. This was fed by policy establishing fire exclusion as the single goal. Over the years, knowledge has dramatically increased regarding the natural role of fire in natural ecosystems and that fire exclusion is not sustainable and desirable. But, the wildland fire management culture has not grown accordingly.

Today’s wildland fire management culture is seemingly blurred between two contrasting perspectives. On one hand is the belief that all wildland fires are bad and should be treated as emergencies. In this perspective, swift, aggressive suppression is viewed as the only acceptable response to every fire, with no regard given to vegetative type, location, values threatened, and resource management objectives. On the other hand, realizing that some fires can benefit ecosystems warrants evaluation of site-specific conditions and objectives. Appropriate responses developed on a case by case basis, when conditions allow, support land management and broader objectives. A culture built on a fire service suppression-only program is not consistent with land and resource management and the guiding framework set forth in the National Cohesive Strategy. Simply put, the relationship of the Cohesive Strategy goals and land management to our culture is undeniable. It has be realized that in the complex wildland fire management system, the Cohesive Strategy has become the foundational doctrine (Christiansen 2019). A more comprehensive culture reflecting all the goals of the Cohesive Strategy must be embraced.

What can be done?

- Strengthen the learning process.

- Increase awareness of the importance of learning to management programs.

- Make lessons learned and important experiences more accessible to wildland fire management personnel and translate their applicability to future scenarios into training and education.

- Expand wildland fire management culture to be more inclusive of the interrelationships of wildfire response, fire-adapted communities, and landscape restoration and maintenance.

Preparedness for Future Scenarios: Falling prey to hindsight bias while trying to understand how the present relates to the past and tending to display overconfidence in the ability to identify and anticipate future outcomes occur too often. The luxury of planning for just a single desired future state while moving forward into such a rapidly changing future cannot be afforded. Future scenarios must be predicted and how work will be done must be reimagined. Wildland fire management must be expected to continue to present new and unique situations that involve increasing fire environment changes and associated issues. A range of futures, some uncontrollable, that could result from interactions among a number of factors must be imagined and prepared for. Simply put, a closer look into the imaginable spectrum of future wildland fire scenarios is needed and knowledge, experience, and perceptions must be challenged with new ideas put into practice.

Unimagined and unprepared scenarios are already becoming commonplace. Recent fires are exceeding historical fire behavior experience. The most recent Australia fire season left a path of extensive destruction far beyond what was imagined. The current worldwide COVID-19 pandemic has occurred with unforeseen swiftness and severity that is forcing every fire management organization around the globe to adapt protocols to ensure continuity in wildland fire management capability. A true evaluation of the full effects of this pandemic on wildland fire response sustainability will not be possible for a year or more. But it is a certainty that response protocols and many aspects of wildland fire management will change from historical norms.

What can be done?

- Imagine and identify future scenarios and effects on wildland fire management.

- Plan and prepare for eventualities associated with climate change, abnormal fuel accumulations, socially impactive issues, other possible external influences, such as pandemics, and the impacts of politicization of fire management and oversight during periods of crisis.

- Support research to help identify future scenarios.

- Think outside the box and develop new ranges of appropriate strategies and tactics (Roper 2020).

Social and Political Realities.: Society is an increasingly important stakeholder in wildland fire management decisions and actions. Fire management is no longer a remotely-based program primarily associated with wilderness, roadless, and remote areas. It has become and forever will be part of a population-based paradigm associated with urban areas, wildland-urban interface areas, and managed public lands mostly visible by much of society. There is greater threat to and involvement of structures in unplanned fires today and, it is likely that for most careers, this threat will never be this low again. Social awareness of wildland fire is rising and with it, expectations are greater than ever before. Political attention, scrutiny, and involvement are higher than at any previous time and can only be expected to heighten into the future.

Social and political expectations have substantial effects on management options. They drive unwise actions that may compromise risk management and increase exposure to firefighters and equipment, escalate expenditures, and conflict with ecological objectives. More frequently, society is expecting protection, fire suppression, and the use of airtankers, regardless of the situation.

Adapting to, overcoming, and learning to deal with social and political influences as a norm is imperative. Anticipating, responding appropriately, and incorporating these influences in wildland fire management must be routine. The COVID-19 pandemic is a graphic example of the onset of a new external social influence that abruptly and dramatically increased challenges. It forced new thought processes to identify and put into practice new protocols, both for the protection of firefighters and the public (Roper 2020).

What can be done?

- Adapt to working in an environment based on social – ecological – and political interrelationships.

- Expect and anticipate significant social influences to develop as realities that increase current and future challenges.

- Reimagine the influence of future social realities and prepare for these eventualities.

Ecological Realities.: Ecological realities facing fire managers today include the interrelationships of climate, vegetation, and fire and how they affect the fire environment. Vegetation structure and composition and fuel accumulation are significantly important areas. In a large number of national reports discussing wildfire problems and future actions, a common assertion is that the most extensive and serious problem related to the health of wildland areas is the over-accumulation of vegetation and burnable fuels. This situation is partly responsible for the increasing number of large, intense, uncontrollable and highly destructive wildland fires (USDA-USDI 2014).

Changing climatic conditions are setting the stage for worsening fire seasons. Drier conditions during winter precipitation periods coupled with longer, hotter summers favor earlier starting fire seasons with longer durations. Climate models are projecting these conditions as a common pattern in coming years.

In recent years, increases in record breaking temperatures and recurring droughts have led to shifts in wildland fire around the world. Ample evidence already exists of climate-driven fire regime change and resultant worsening effects. Annually, reports describing the severity of fires and fire seasons are appearing more frequently. In 2020 and 2019 striking headlines about wildfires were frontpage in Australian news releases. In 2019 and 2018 news releases highlighted the frequency and severity of fires across Sweden, Russia, Greenland, Canada, California, and Alaska with the most expensive and largest fire years ever recorded in 2018 in California and British Columbia. Climate change consequences are here today, not in the distant future, and they are escalating.

Fuels are the only element in the fire-vegetation-weather-topographic dynamic that managers are able to modify. Improving protection capability involves treating fuels, reducing potential fire behavior, and increasing the likelihood of successful fire suppression efforts (USDI-USDA 2014). A range of vegetation manipulation techniques and fuel treatment options exist for this purpose.

Prescribed fire, the application of fire under a planned ignition to meet specific objectives to treat natural fuels has emerged as a keystone land management process. Prescribed fire is widely advocated for reducing wildfire hazard and has a long and rich tradition rooted in indigenous and local ecological knowledge (Kolden 2019). It can reduce potential fire behavior, increase the potential success of suppression efforts, and maintain and improve ecosystem health and resiliency. It can be completed at scales ranging from site-specific to landscape and range from single to combinations of treatments, and single to multiple applications over time.

As a result, prescribed fire is highly versatile. But current application levels are failing to have major impacts on widespread fire behavior. Seventy percent of prescribed fire in the US has been reported to be in the southeastern portion of the country, equating to over twice the amount as the entire rest of the country between 1998 and 2018 (Kolden 2019).

Managing unplanned fires for resource objectives and ecological purposes refers to a strategic choice to use unplanned ignitions to achieve resource management objectives (USDI-USDA 2014). This management option has strong potential but has failed to be applied in many potential areas of opportunity. But, while an extremely useful tool for managing fire-adapted ecosystems and achieving fire-resilient landscapes, it has never received uniform endorsement and does have limited potential in some land ownerships because of statutory constraints.

What can be done?

- Improve awareness of the value of prescribed fire and other fuel treatments.

- Improve capability to plan and implement prescribed fire and fuel treatments.

- Improve the ability to plan, implement, and evaluate ecological effects of prescribed fire treatments in achieving short- and long-term objectives at all spatial and temporal scales.

- Develop a better understanding of the relationship of prescribed fire to human values.

- Improve communication and collaboration activities among governmental units, the public, and partner organizations.

- Establish and maintain a strong and efficient link between research and management.

- Accelerate the application of prescribed fire, managing wildland fire for resource objectives, where possible, and non-fire fuel treatments.

- Better prepare communities to withstand wildfire.

5. Evolving our system to face the future

This analysis and proposal by no means, meant as a criticism of wildland fire management. Instead, it is intended to help illuminate considerations and possible steps to build a more efficient and comprehensive pathway for the future. It is a synopsis of perspectives on how the fire management system should respond to changing complexity with focus on areas were attention is warranted. In the course of program history, many successes have been realized, many milestones have been achieved, and many efforts and activities have been well-directed, passionate, and committed. But, it cannot be overemphasized that resting on these gains while conditions continue to change will be unproductive and place the program and its people at a severe disadvantage.

Tendencies indicative of tomorrow’s wildland fire environment underscore a need to broaden wildland fire management latitude. Proactive actions are and always will be necessary. Increasingly frequent and damaging wildfires cannot simply be accepted as unavoidable events. Knowledge, experience, and perspectives must be continually challenged. Accelerated learning must occur and drive planning, preparedness, and implementation for a range of future scenarios, some that may be outside of our control. Expanded ecological knowledge must not go unnoticed, and must be used in the shaping of management activities along with other scientific and technological advancements.

Fire management cannot fall victim to hindsight bias while trying to understand how the future may relate to the past. The ability to identify and anticipate future outcomes and avoid planning for a single desired future state must be expanded. Expecting that the business of wildland fire management will continue to present new and unique situations; being aware that the fire environment will continually change; and being prepared to encounter associated unforeseen issues has to become the standard. Simply put, constantly looking into the imaginable spectrum of future wildland fire scenarios must become the norm. Actively seeking to not be surprised, striving to anticipate most, if not all, potential future scenarios, and planning proactively need to be the reality. Future scenarios will directly influence all aspects of management realities, be closely tied with social and political realities, and affect the ability to maneuver through ecological realities. Moving ahead, there is much that can be done. As is commonly said, thinking must occur “outside the box.”

The wildland fire management system is a complex system. The emphasis here has been to illuminate the importance of preventing the system from falling into stasis, or worse – to face these changing and increasing risks by multiplying the strategies and tactics inherited from the past, because they once worked and because, quite frankly, there are challenges in our fire future that appear insurmountable. Continual advancement and modernization based on infusion of emerging science and technology with the best available information, support tools, and processes is needed. Adapting to change, overcoming obstacles, and expanding capabilities – with reliance on historic approaches when appropriate is vital. But if the current fire management system, renowned for innovation and success amid adversity, is to transition to a system prepared for future success, then our energies, talent, and funding must be directed into developing and sustaining greater overall capabilities.

Authors: Tom Zimmerman and Joe Stutler are retired employees of the US Forest Service who were fortunate enough to have long careers in wildland fire management. Collectively, they have worked at all levels of the organization and served on Incident Management and Area Command Teams with a combined experience in excess of 100 years. What is offered here is by no means a full prescriptive analysis of the state of wildland fire management but represents the authors’ observations, thoughts, and perspectives about the needs of our wildland fire management system in these changing times. Tom Zimmerman is Strategic Coordination Advisor and Past President of the International Association of Wildland Fire and Joe Stutler is Senior Advisor for Deschutes County, Bend, OR.

References

Agrawai, Saprana, Aaron DeSmet, Sebastien Lacroix, and Angelica Reich. 2020. To emerge stronger from the COVID-19 crisis, companies should start reskilling their workforces now. McKinsey and Company. McKinsey Insights.

Archer, Michael. 2019. Rapid initial attack, the wave of the future? Air Attack (Issue 6): 91-101.

Bosworth, Dale, and Jerry T. Williams. 2018. A failure of imagination: why we need a commission to take action on wildfire. p 101–103. (In): 193 Million Acres: Toward a Healthier and More Resilient US Forest Service. (Ed) Steve Wilent (Society of American Foresters. Washington, D.C).

Calkin, D.E., M.P. Thompson, and M.A. Finney. 2015. Negative consequences of positive feedbacks in US wildfire management. For. Ecosyst. 2(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/ s40663-015-0033-8.

Calkin, David E., Jack D. Cohen, Mark A. Finney, and Matthew P. Thompson. 2014. How risk management can prevent future wildfire disasters in the wildland-urban interface.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA January 14, 2014 111 (2) 746-751.

Christiansen, Vicki. 2019. Opportunities to improve the wildland fire system. Fire Management Today. 77(3): 5-10. USDA Forest Service. Washington, D.C.

Cissel, John, and Tom Zimmerman. 2018. A future without the Joint Fire Science Program? Wildfire: 27(4):16-20.

Fire Executive Council. 2009. Guidance for Implementation of Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy. National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC). Boise, ID, USA. 20 p.

Hall, John, Paul Steblein, and Colin Hardy. 2018. Living with wildland fire in America. Building new bridges between policy, science, and management. Wildfire: 27(3):16-18.

Ingalsbee, T. 2017. Whither the paradigm shift? Large wildland fires and the wildfire paradox offer opportunities for a new paradigm of ecological fire management. Int. J. Wildland. Fire. 26(7):557–561. doi:10.1071/WF17062.

Kolden, Crystal. 2019. We’re not doing enough prescribed fire in the western United States to mitigate wildfire risk. Fire: 2,30 10 p.

Rains, Michael and Thomas Harbour 2018. Restoring fire as a landscape tool. p 129–164. (In): 193 Million Acres: Toward a Healthier and More Resilient US Forest Service. (Ed) Steve Wilent (Society of American Foresters. Washington, D.C).

Roper, Bob. 2020. Wildfire and the pandemic – what’s ahead? (Western Fire Chiefs). A statement by Bob Roper for the western Fire Chiefs’ Association. April 1, 2020. In press to be reprinted in Wildfire 29(2):

Shultz, Courtney, Matthew Thompson, Sarah McCaffrey. 2019. Forest Service fire management and the elusiveness of change. Fire Ecology (2019):15:13.

Thornton, Richard. 2020. Commentary: More of the Same Won’t Help. Wildfire 29.1:37-39.

Thompson, Matthew P., Donald G. MacGregor, Christopher J. Dunn, David E. Calkin, and John Phipps (2018). Rethinking the wildland fire management system. Journal of Forestry 116(4):382-390.

Thompson, M.P., D.G. MacGregor, and D.E. Calkin. 2016a. Risk Management: Core Principles and Practices, and their Relevance to Wildland Fire. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS- GTR-350. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, CO. 29 p.

U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDI-USDA]. 2014. The national strategy: the final phase in the development of the national cohesive management strategy. Washington, D.C.: 101 p. http://www.forestsandrangelands.gov/strategy/documents/strategy/CSPhaseIIINationalStrategyApr2014. pdf.