A deep-time fire ecologist explores the history, policy and practices of fire in the heart of America’s prescribed fire landscape.

An essay-review by Johnny Stowe

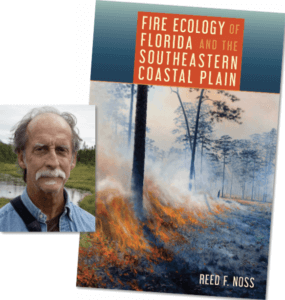

In “Fire Ecology of Florida and the Southeastern Coastal Plain,” Reed Noss has given lovers of the firelands of Southeastern North America another well-written book of immense value.

As a land manager ever-reflecting on ways to better use fire as a tool for restoring and maintaining South Carolina’s heritage preserves, as well as on my own farm and the lands of others, this book helps me get things done where it counts most: on-the-ground. Noss answers many of the questions that have arisen in my mind in a half-century of burning wild lands, and in discussions with policy makers, land managers and ecologists, and he deals well with other issues that I have never thought about.

Reed’s book has been particularly helpful to me in dealing with public concerns over conducting prescribed burns in the growing season, which in my part of the world coincides with the thunderstorm season as well as the period when ground-nesting birds are laying eggs and raising young. This late spring through mid-summer period is when lightning-ignited fires first shaped the ecosystems and landscapes of the Southland, long before human-ignited fires came into play.

Noss tells well the story of how soils, water and fire interacted during a period of climatic shifts to shape the vegetation and wildlife of the southeastern coastal plain, most particular in Florida. Using an evolutionary lens, he reveals how grassland birds, including bobwhite quail and other imperiled species, have evolved to prosper in a frequent-fire regime in which growing-season fires sometimes directly impact nesting.

Paradoxically, although regrettably sometimes nests are lost to fire, growing-season burns yield habitat benefits that outweigh the costs, with numbers of individuals in an area overall – i.e. at the population and landscape level – increasing. In a densely populated and highly fragmented landscape where allowing lightning-lit fires to burn is seldom a safe or effective option, and fires must be lit under prescription, having a rigorous work of scholarship that advocates for spring and summer burning is invaluable. Noss’ book provides an altogether welcome voice of reason to an issue too-often dominated by an emotional, Bambi-esque, anti-management fringe. The less time Southern firelighters spend dealing with polemics the more opportunities we have to burn our savannas, woodlands and forests for the myriad, interconnected and synergistic public safety, economic, ecological and cultural benefits that frequent fire provides us.

Noss applies key critical thinking skills, developed over many decades as an academic researcher as well as a conservation practitioner, as he makes firm arguments in places, while qualifying statements for which the evidence is less clear or when he is giving his intuitive opinion. Throughout the work, what shines through is his keen field observations based on many years studying and visiting fire-dependent ecosystems and talking with the people who burn them; his broad, deep and tight scholarship; and his thorough familiarity with the ecological literature.

This latest book, like his wonderful “Forgotten Grasslands of the South: Natural History and Conservation,” begins with deep-time, evolutionary explanations of how these special landscapes have come to be, including historical evidence enchantingly told and inspiring, and then delves into why and how we should protect them, both for their intrinsic value as well as their broad range of benefits to humans.

As an ecosopher (ecological philosopher) in the vein of Aldo Leopold, as a naturalist whose hero is the first modern fire scientist Herbert L. Stoddard, as a passionate lover of all things wild and free, and as a paragon scientist, Reed’s latest book (like his “Saving Natures Legacy: Protecting and Restoring Biodiversity”, co-authored with Allen Cooperrider) is a work that will benefit not only land managers and policy makers, but all wildlife biologists, foresters, botanists and others who seek to ensure special places remain that way.

Noss explores the weave of fire and human history, and the challenge of managing our lands with fire, writing:

In Florida, despite better public acceptance of fire than in perhaps any U.S. state, the surge of newcomers from less fire-prone regions and the rapidly increasing urbanization and highway network now complicate controlled burning and smoke management. These changes raise serious questions about the extent to which fire will be part of our environment in the future. One thing we know for certain, however: without fire, our landscapes would be much poorer biologically and less attractive aesthetically. Without frequent burning, some natural communities would degrade to a condition where more severe and potentially dangerous fires are bound to occur. It is incumbent on naturalists and conservationists to serve as fire advocates and ambassadors and to use evidence-based arguments to promote rational fire management. (5)

Reed’s timeless books — whether read for pure enjoyment, used as textbooks and references for students and others, to inform management, or as tools for policy — will endure and shape the lands he loves far into the future.

+

About the Author

Johnny Stowe is a forester who lights fires in Southeastern North America, and he’s a new board member with the IAWF (see IAWF News for a full bio).